The Highlight Report has been a staple of project management for decades: a one-page summary of the week with a RAG view of schedule and budget, key risks and issues, and space to flag concerns for stakeholders. Simple, visual, reassuring. But in an age of live dashboards, agile ceremonies and AI copilots, is the Highlight Report still the best way to keep people informed — or an artefact past its prime?

Where a Highlight Report still earns its keep

- Crispness. Turning a sprawling project into one page forces clarity: what moved, what slipped, what’s blocked — and why.

- Consistency. Senior leaders value a standard format across projects. Comparable RAGs and familiar headings help them spot patterns and escalate quickly.

- Formality. The act of writing a weekly highlight creates a pause for reflection. It nudges the team to step back from the noise and ask, “What really matters this week?”

- Accountability. A dated record of status, decisions, risks and actions removes ambiguity about who knew what, and when.

Where it creaks

- Lagging, not leading. By the time a report is drafted, reviewed and circulated, the picture may have moved on.

- One-way traffic. Traditional highlights broadcast status rather than invite decisions.

- Duplication. If delivery already lives in Jira, Azure Boards, Trello and a portfolio dashboard, a separate highlight can feel like a second job that adds little.

- RAG theatre. Red/amber/green can oversimplify, hiding risk until too late.

Highlight Report vs Dashboards, Agile ceremonies and AI

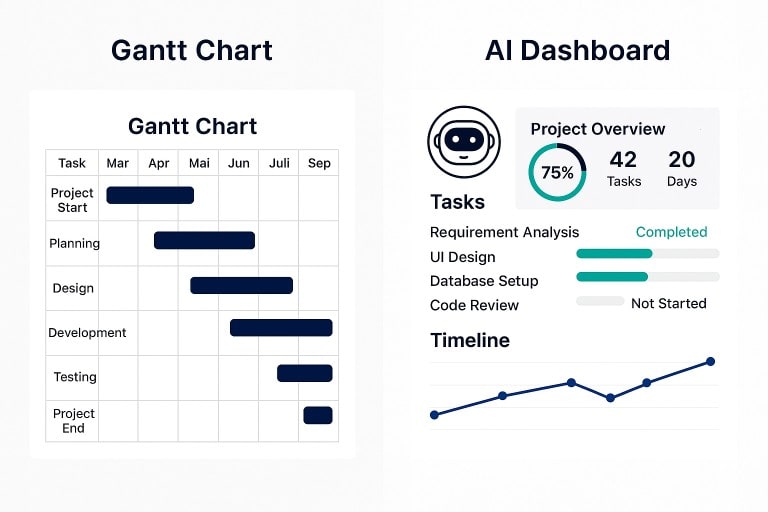

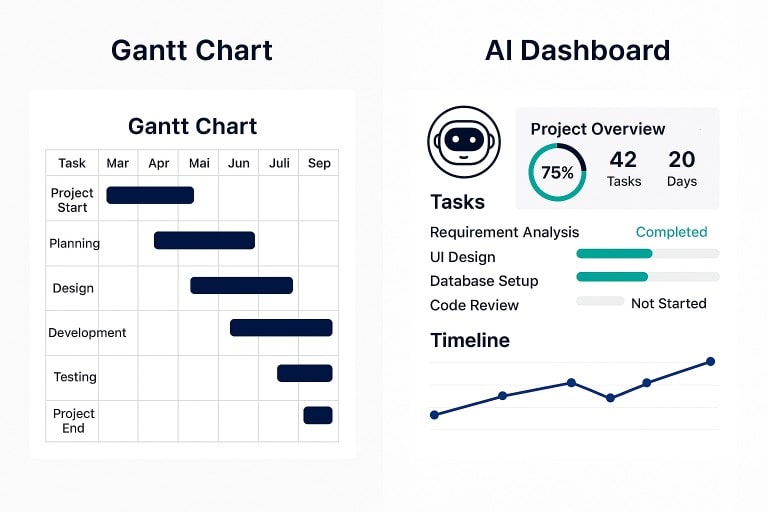

- Dashboards. Always-on visibility straight from delivery tools sounds ideal — but raw dashboards often overwhelm. They still need interpretation.

- Agile ceremonies. Sprint reviews and demos show real progress — but they don’t replace a portable executive summary. They still need synthesis.

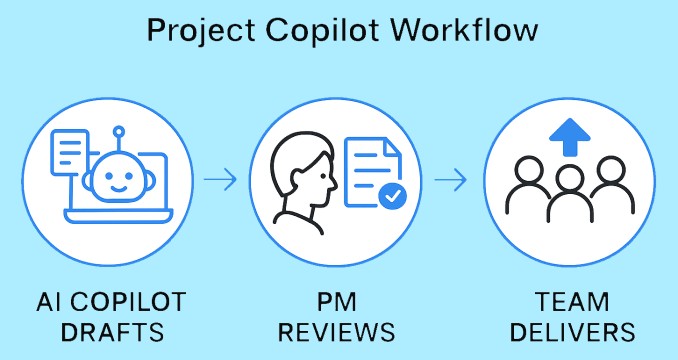

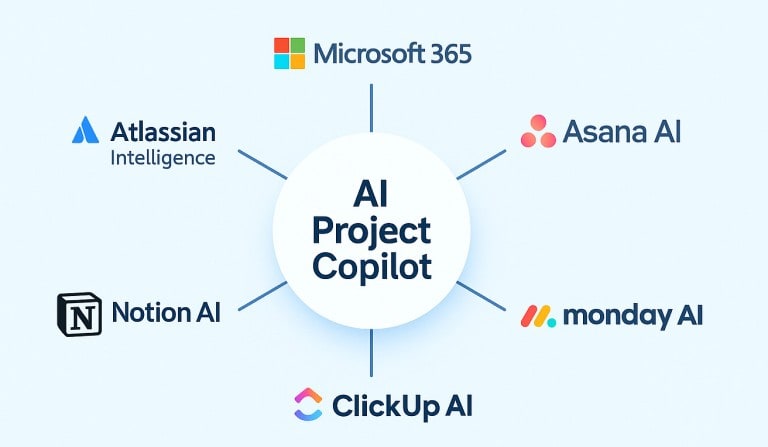

- AI copilots. Drafts from tasks, commits and threads help — but still need judgement.

The middle ground that works today

- Make it decisional. Shift from weekly history to an executive decision log.

- Embed live data. Link to dashboards; keep report text light and interpretive.

- Keep it to one screen. Use links for detail.

- Standard headings, human voice. A consistent structure with a natural tone.

- Timebox the work. Cap prep at ~30 minutes.

A modern Highlight Report template (steal this)

- This week at a glance — two sentences max.

- Decisions & asks — bullets with owners and dates.

- What changed — scope, dates, spend; only the deltas.

- Risks & mitigations — top three; clear trigger, impact, owner.

- Next week’s focus — what we’ll actually do.

- Links — dashboard, backlog, RAID log, latest demo.

- Optional sponsor note — interpretation from PM.

When a Highlight Report is the wrong tool

- Ultra-fast work: daily shifts make weekly highlights laggy.

- Single stakeholder, high touch: a report may be redundant.

- Strong portfolio reporting: consider a monthly narrative instead.

When it earns its keep (again)

- Cross-organisation programmes.

- High-stakes delivery.

- Distributed stakeholders.

Practical pitfalls (and fixes)

- Everything is ‘in progress’ → Focus on outcomes.

- RAG drift → Define criteria and explain changes.

- Copy-paste fatigue → Automate inputs, spend human time on interpretation.

- No follow-through → Track last week’s decisions/actions.

So… does it still work?

- Yes — if you treat it as a concise decision brief, not a weekly diary.

- The modern Highlight Report is one screen, linked to live data, and explicit about what you need from leadership.

- If your stakeholders value it, keep it and sharpen it.

- If they already swim in dashboards, your highlight may simply be the commentary.